Main Second Level Navigation

- Welcome

- Why Toronto?

- History of the Department

- Vision & Strategic Priorities

- Our Leadership

- Our Support Staff

- Location & Contact

- Departmental Committees

- Department of Medicine Prizes & Awards

- Department of Medicine Resident Awards

- Department of Medicine: Self-Study Report (2013 - 2018)

- Department of Medicine: Self-Study Report (2018 - 2023)

- Communication Resources

- News

- Events

Chair's Column: Taking Stock of the Department’s Mentorship Program: Are we there yet?

Success in academic medicine is influenced by the quality and quantity of mentorship, sponsorship, role models and social networks, by one’s personal circumstances and access to resources, yet these essential ingredients for success are not shared equally and equitably among department members. Formal mentorship programs have been encouraged to overcome these inequities (Sambunjak D, Straus SE, Marusic A. JGIM 2010).

In 2015, the department established a formal mentorship program, putting into place processes to enhance mentorship and incorporating responsibility for ensuring effective mentorship into the position descriptions of all departmental leaders. Since then, our faculty surveys have been an important source of feedback regarding whether the mentorship program is helping you achieve your career aspirations. We’ve documented an increase in the proportion of faculty who are receiving mentorship (from 47% in 2017 to 76% in 2022) and increased satisfaction with mentorship (from 66% to 74% over the same period).

A great start. But the mentor-mentee relationship is complex. Mentors may play many roles in academic medicine such as task-specific mentoring, e.g. grant preparation, career planning, and personal skills development (e.g. conflict resolution, emotional support and advice). Mentors can also act as sponsors – to advocate and create opportunities for mentee’s ongoing growth, recognition and promotion. Little is known about what makes mentorship effective from the perspective of mentees.

So, we asked you.

You may recall that in our 2022 Faculty Survey, we asked you a series of questions about your mentorship experiences:

- Did you have a mentor? If so, did you have a formal (assigned) mentor or an informal mentor or perhaps both?

- Were you satisfied with the mentorship you were receiving?

- Did you find your mentor sensitive to your needs?

- Was the mentor doing a good job assisting you with career planning, managing work-life balance, navigating institutional culture, dealing with sensitive or challenging issues, and helping build your self-reflection abilities?

- And to what extent was your mentor being a sponsor/advocating for you and networking/opening doors to help you pursue desirable professional activities?

To enable us to look for differences in mentorship experiences by gender or race/religion/ethnicity, we asked if you felt under-represented in medicine (URM) based on race/religion/ethnicity. From your responses, we examined the extent to which the areas of mentorship assessed explained satisfaction with mentorship, controlling for differences in rank, year of appointment, gender and URM status.

We are extremely grateful to the 540 full-time faculty members (59.5% of those surveyed) who responded. Among our respondents, 59 (11%) self-identified as URM females, 176 (33%) as non-URM females, 47 (9%) as URM males and 257 (48%) as non-URM males.

What did we learn?

76% reported receiving mentorship – 2/3 formal and 1/3 only informal mentorship. The proportion reporting receipt of mentorship was highest among our youngest faculty members (< 40 years - 91.5%) and declined with increasing age to 51% among faculty members aged 70+ years. URM faculty were more likely to be receiving formal mentorship (83%) than their non-URM (non-URM females 77% and non-URM males 72%).

Among the 411 with mentors, 74% were somewhat or very satisfied with their mentorship. 40% had a mentor sensitive to their needs. Most agreed their mentor had helped them navigate institutional culture (69%) and foster self-reflection abilities (62%). 47% indicated their mentor had been effective in helping them manage challenging issues, while 45% and 40% agreed their mentor had helped them manage work-life balance and had been a sponsor, respectively. 39% indicated their mentor had been effective in helping with career planning.

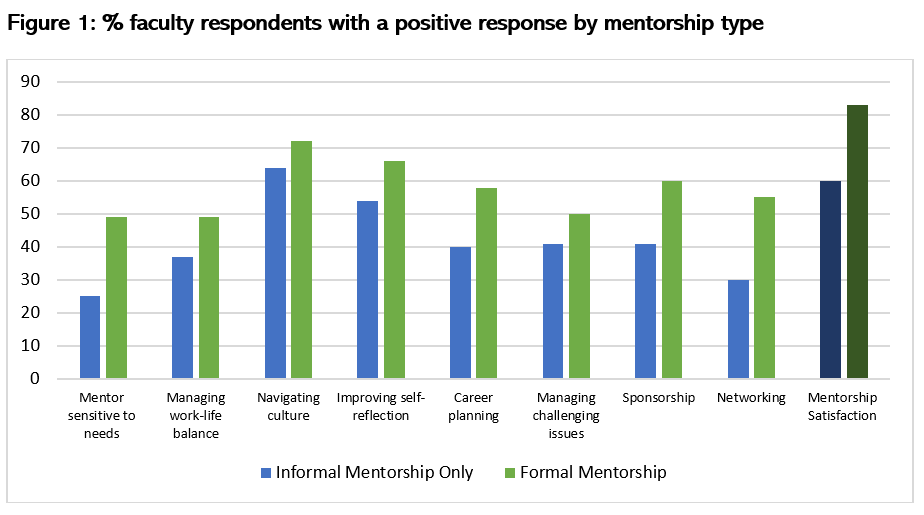

Those with a formal mentor were more likely than those with informal mentors to receive effective mentorship and to indicate they were satisfied with their mentorship.

For all areas assessed, e.g. help with self-reflection, a positive response was associated with a higher likelihood of being satisfied with one’s mentorship. In multivariable analysis, four aspects of mentorship were independently associated with mentorship satisfaction.

These were help from a mentor with:

- Self-reflection abilities (adjusted OR 2.61, 95% Confidence Interval, CI, 1.75-3.87).

- Managing challenging issues (adjusted OR 1.87, 95% CI 1.28-2.73).

- Sponsorship (adjusted OR 1.85, 95% CI 1.28-2.73).

- Career planning (adjusted OR 1.69, 95% CI 1.17-2.44).

For help with managing difficult issues, career planning and sponsorship, the relationship with mentorship satisfaction was stronger in female and URM faculty than in their male and non-URM peers. For example, the odds of being satisfied with mentorship given the mentor had been a sponsor were 1.86 times higher among URM females (adjusted OR 2.79, 95% CI1.38-5.63) compared with non-URM males (adjusted OR 1.50, 95% CI 0.95-2.37). This makes sense given prior faculty survey findings, which showed that female and URM department members were more likely than their male and non-URM colleagues to indicate they felt excluded from social networks and needed to work harder than others to be perceived as legitimate scholars (Pattani R et al Medical Teacher 2022).

For help with self-reflection abilities, the strength of the association with mentorship satisfaction went in the opposite direction. The odds of being satisfied with mentorship given the mentor had helped with self-reflection abilities were 1.94 times higher in non-URM men (adjusted OR 3.34, 95% CI1.93-5.78) compared with URM females (1.72, 0.86-3.47).

Take home messages:

These findings support ongoing attention to how we support our faculty members across the academic career lifespan. They indicate the following:

- Formal mentorship appears to be more effective than informal mentorship.

- Continued efforts are required to expand opportunities for formal mentorship among mid and late-career faculty members.

- Although they play many roles, we need to ensure our mentors are equipped to provide their mentees support with self-reflection, managing difficult issues, and career planning, and that they serve as sponsors. Given the proportions indicating they had received support in these areas, we have room for improvement.

- The gender/URM differences observed were not statistically significant, likely due to the relatively small number of faculty who self-identified as URM. Still, the apparent ‘dose response’ relationship seen suggests a one size fits all approach toward mentorship is unlikely to result in mentee satisfaction. Elucidating the mentee’s mentorship priorities has potential to further improve faculty members’ mentorship experiences.

Thank you to all the people who have contributed to advancing mentorship in the department, including our most recent Lead for Mentorship, Catherine Yu.