Main Second Level Navigation

- Welcome

- Why Toronto?

- History of the Department

- Vision & Strategic Priorities

- Our Leadership

- Our Support Staff

- Location & Contact

- Departmental Committees

- Department of Medicine Prizes & Awards

- Department of Medicine Resident Awards

- Department of Medicine: Self-Study Report (2013 - 2018)

- Department of Medicine: Self-Study Report (2018 - 2023)

- Communication Resources

- News

- Events

Womb-Mates: U of T Professors, Alumni and Twins Jay and Ed Keystone Pay it Forward

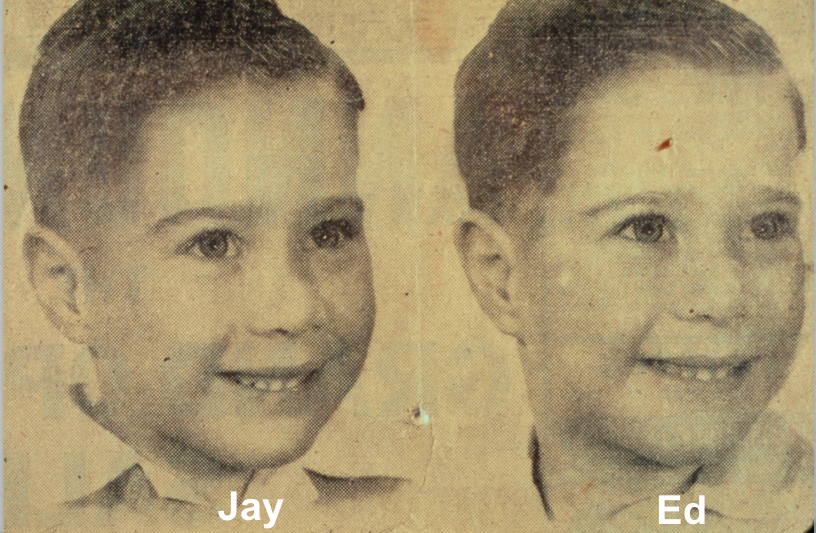

Drs. Jay and Ed Keystone

Professors of Medicine Jay and Ed Keystone, both BSc ’65, MD ’69, are esteemed clinicians, researchers, educators and mentors — and foremost experts in their respective fields. Jay, an infectious diseases specialist at University Health Network, is a member of the Order of Canada, and Ed is a Master of the American College of Rheumatology. They reflect on the people who got them to where they are today, and what it means to pay it forward.

Professors of Medicine Jay and Ed Keystone, both BSc ’65, MD ’69, are esteemed clinicians, researchers, educators and mentors — and foremost experts in their respective fields. Jay, an infectious diseases specialist at University Health Network, is a member of the Order of Canada, and Ed is a Master of the American College of Rheumatology. They reflect on the people who got them to where they are today, and what it means to pay it forward.

In 1943, we were "womb-mates" for a mere seven months, entering this world together weighing a total of six pounds. We later found ourselves failing in public school. Not because we were bored, but because we were not very bright. We are the same students who were told by our public school principal that we would never get to university. The same mediocre high school students who, later, through sheer hard work, graduated at the top of our medical school class and who have since enjoyed academic careers in the Faculty of Medicine at this great university.

What is our point, you ask? Our point is this: it doesn’t matter where you begin or even how well you begin, but where you end up. And, recognizing the help of the people who got you to where you are, it’s up to you to pay it forward to those who will come next.

So, how could two mediocre students find their way into the competitive world of medicine? We started our university careers in commerce and finance at U of T, from which we extracted ourselves at the beginning of second year. We had received advice from a newly graduated physician from the University of Michigan, our cousin, Jay Allen Keystone.

“Why don’t you go into medicine?” he asked.

“Because only students dedicated since toilet training and Ontario Scholars go into medicine,” we answered.

His response changed our lives: “Dedication in medicine is important when you come out, not when you go in.”

With this lesson from his experience as a new physician, he paid it forward.

Academic institutions are not homogeneous, and neither are the departments within them. One of the first lessons we learned about academic medicine is that, apart from ability, there are two ways to succeed: you can step on or over your colleagues in your quest to reach the top, or you can be kind and fair to those with whom you work.

Treating colleagues equally and with kindness has been a rule that we have diligently followed throughout our careers. This philosophy has paid us both enormous dividends. We have been given unexpected opportunities in leadership positions in our specialty societies and the university. Not because we are brilliant (we are not), but because we treat our colleagues, whether specialists or not, with respect, and have always been very supportive and attentive to their requests for assistance.

One notable anecdote comes to mind: When Jay received his stem cell transplant from his “spare parts clone” brother Ed at Princess Margaret Cancer Centre, he was visited by several colleagues from Toronto General Hospital and, unexpectedly but appreciatively, by a maintenance man who learned about his illness and came to provide support. Similarly, when he was admitted to Toronto General Hospital repeatedly this year, senior nurse administrators with whom he worked many years ago on the general medical wards provided invaluable support. Treat people well, and you will be well treated.

One notable anecdote comes to mind: When Jay received his stem cell transplant from his “spare parts clone” brother Ed at Princess Margaret Cancer Centre, he was visited by several colleagues from Toronto General Hospital and, unexpectedly but appreciatively, by a maintenance man who learned about his illness and came to provide support. Similarly, when he was admitted to Toronto General Hospital repeatedly this year, senior nurse administrators with whom he worked many years ago on the general medical wards provided invaluable support. Treat people well, and you will be well treated.

As medical educators, it is our job to train the next generation to be better physicians than we were. Basically, to “train ourselves out of a job.”

There were many wonderful educators who came before us. At the University of Toronto, Arthur Scott, MD ’53, taught us how to solve medical problems from first principles utilizing basic physiology. Hugh Smythe, MD ’50, taught rheumatologic physical examination, following which Ed now teaches rheumatology fellows all over the world to do an expert joint exam. Joe Marrotta, an outstanding clinical neurologist at St. Michael’s Hospital taught us to evaluate neurological events first anatomically and then functionally in the days before CT and MRI were even on the horizon. His colleague Peter Kopplin, MD ’63, the quintessential, caring and consummate internist who, in his quiet, understated way, demonstrated the importance of the doctor-patient relationship.

And finally, Bob Goldsmith, a tropical medicine expert from University of California, San Francisco encouraged his colleagues (namely Jay) to step down from leadership positions “sooner than later” to allow younger clinicians to take over and make their mark. It is very important, and often difficult, to know when it is time to step back for the next generation, a subtler form of paying it forward.

Someone once wrote, “A good education can change anyone, but a good teacher can change everything.” We have tried to give the next generation the benefit of our experience and knowledge, inspired by those outstanding clinicians who came before us.

Our lesson to everyone reading this is to think about the people who made an impact or provided you with mentorship, and how you can pay it forward to others.

Dr. Jay Keystone passed away on September 3, 2019. He was a mentor to generations of trainees, and a respected colleague, teacher, and friend to many. His impact on clinical care has been immense. He will be missed. In memoriam: Professor Jay Keystone